|

|

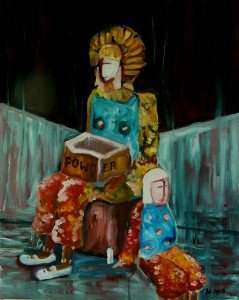

Old Jester and Young Harlequin

|

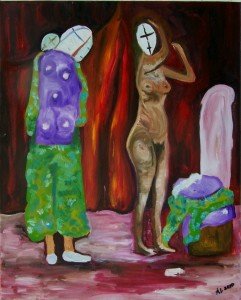

Background: I have translated artists’ works on war, migration, desolation and isolation, in particular with reference to works featuring pierrot, harlequin, clown or acrobat figures, precursor to our present day ShortKnee. ShortKnee can be traced back to the spoken word traditions of the West African Chantuelle, oral libraries whose recollections made bearable the suffering of slaves on the plantations of Grenada, fused with French Pierrot elements, and wrapped in six and a half yards of vulgar fabric that is breathtaking in sunlight masquerade. Once a disguise and way to compromise, the ShortKnee is today, in this artist’s opinion, the most compelling icon of Grenada. These are part of my Chantuelle Translations series, articulating my response to the socially sanctioned slow and painful death of our indigenous artform.

|

|

Harlequin’s Family

|

Walking, jumping chanting. The ShortKnee is iconic of Grenada’s annual carnival. Under painted mesh masks, white head towels, and yards and yards and yards of fabric caught up just under the knees and around the wrists, fabric in seriously unfortunate teeth-gnashing patterns that can only be made breathtaking in a ShortKnee masquerade. The players become ‘one in spirit with the masks’, and in the early days, were known to rush in waves into neighbouring villages to settle old scores, a beautiful terror, sunlight flashing off the chest mirrors, chanting calling out the misdemeanours of the day, names, people, places, tens of ankle-belled feet accompanying in sinister beat on hot dirt and asphalt. Once their business was complete, the tide receded in a screech of whistles under cover of mists of baby powder.

|

| Acrobat and Young Harlequin |

The ShortKnee is, or used to be generational mas, not so much handed down, as in the new players were brought up into it, to understand the characteristics and talismans required of the ShortKnee. Played once a year, and only for a few days, without a more visual approach, ie the use of this icon as artistic subject, the truth of the ShortKnee – from tribal masquerade to carnival clown, and the reasons behind their songs – may cease to exist.

In October 2010, I had the opportunity to see the Chester Dale collection at the US National Gallery of Art in DC, among which was Picasso’s Family of Saltimbanques. I could see the grain, and I was quite certain, I could smell the paint as well. Up close and personal, against a barren landscape the harsh aloneness of their life was carefully composed. I realised that this family, and as in several of his other clown/harlequin/acrobat paintings, the figures seem tired, isolated, stuck in a grin-and-bear-it space where they’d rather not be.

|

|

Buffoon and Young Acrobat

|

|

|

Harlequin 1

|

|

|

The Acrobat’s Family With A Monkey

|

Back in studio, my evolving Chantuelle series took another twist. I took about a dozen of Picasso’s Saltimbanque paintings and refashioned them ShortKnee in a more local context, and used a less subdued palette, to see if I could evoke isolation in such a garish mas. The red ground that peaked through saddened the bright colours, communicating blood that was sometimes shed during these village incursions.

|

|

At the Lapin Agile

|

|

|

Harlequin sitting on a red couch

|

|

|

Harlequin and his Companion

|

|

|

Mother and Child

|

The works I translated featured ShortKnee alone and as family, the everyday man, the passing on of elder knowledge, recipients not really caring. My ShortKnee also appear melancholy, and stuck in their grin-and-bear-it space. These are my ShortKnee versions of Picasso’s works created in Paris in the early 1900s. His titles are given for ease of translation. My titles are simply Picasso’s Chantuelles 1, 2, 3 etc.

It has been suggested that the Picasso’s Saltimbanques tell of the alienation of the avant-garde artists, of Picasso and his circle. Do my versions tell the same of our artists?