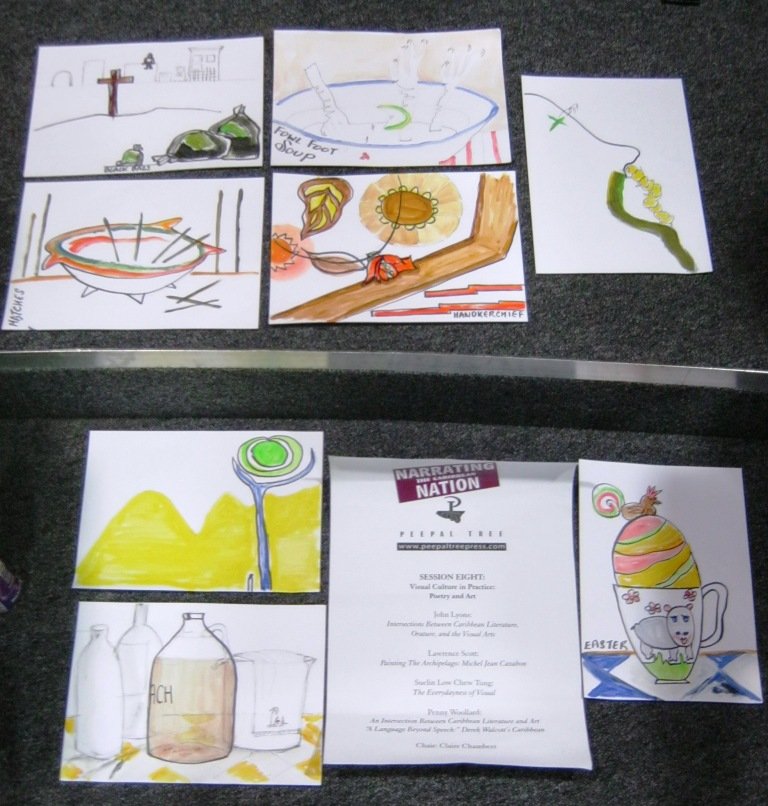

My visit to the UK was to attend and present a paper at a conference in Leeds. My paper on the Everydayness of Visual, accompanied by about nine handcoloured sketches, was part of Session Eight, on Day One of the Narrating the Caribbean Nation conference hosted at Leeds Metropolitan University by Peepal Tree Press. The theme for this panel chaired by Emily Smith was Visual Culture in Practice: Poetry and Art. I shared this panel with John Lyons (Trini author, painter poet and cook), Lawrence Scott (seriously prize winning Trini author, who spoke on Cazabon) and Penny Woollard (PhD candidate at the University of Essex, who spoke on Bearden on Walcott).

Leonard Baskin says ‘Art is man’s distinctly human way of fighting death’. My furious scribbles during the break prior to my panel proved just that – me trying to fight my death-by-stage-fright, by creating new works impromptu to go with my paper, which I abandoned half way through in favour of just talking about what I envision when I write. An extract of the paper follows, with the sketches hastily done in a quiet room, much to the amusement of two other presenters also hidden there revising their works. A photo of me in elegant disarray, I unfortunately do not have.

|

| The scribbles and the panel poster |

The abstract: Grenadian culture, folklore, history, religion and tradition has structured my visual stories of photographic paint can labels of decaying Georgian buildings, collaged Facebook® chats between George Washington and Louis La Grenade about freed coloured men in the land of milk and honey, quick paintings of the lost streets of the capital Saint George’s created in time for its Tercentennial, followed by a series of reinterpreted 18th and 19th century artworks substituting the ShortKnee carnival icon for a Pierrot. These elements also provided strong foundation for an expanding collection of short stories, including A Whiff of Bleach, which captured desperation and loneliness during an intolerable dry season – one of the many fragments of life in a Caribbean island environment – and won me a Commonwealth Regional Highly Commended Short Story award in 2010. This paper proposes to illustrate, using a selection of my compositions as examples the challenge for me as a short-story painter writing short stories, to write as I paint, inspired by the everydayness of the people, places and things of this small island state within the Caribbean Nation.

An extract: I write as I paint, my memories colour inspiration borrowed from our property on top of a triangular ridge protected on three sides by the hills of Saint Paul and Saint George, the sea to the west, and the winding Saint John a hundred feet below, a length of miserable river exposed to a temperamental sun. I paint as I write as I speak, as I see things, and the story they hold. From a collection of photos, a book (like my father’s copy of The Robe, about the aftermath of the crucifixion of Jesus), a T-shirt with so many holes, I am still reluctant to throw out, a thin blanket, a one-eyed toy bear in an apron, a cast iron pot – each item has a story, has a connection to family, friend or a complete stranger. Many of these invisible items I come across walking around town or just passing in a bus, seemingly insignificant items generate powerful images that I try to capture in quick sketches and increasingly more, in words, inspiring me to dig under their surfaces, these invisibles and bring their story to light.

My artist statements are filled with the stories of what I find when I look, and what looks at me, until I find it.

Images juggle and unearth memory, so too, like at our family gatherings at Easter – which I have just missed, and at Christmas, and whenever a member of family returns home for a short visit, we gather together and reminisce, and often discover new connections to things and places with which I surround myself, and which enrich my life.

I am an old people child. Grew up with grandparents, as my parents were abroad studying. So if you know an old people child, you know that they have broughtupsy – they tend to treasure things, and even if in youth they deny this intrinsic caring, in later life, this elder knowledge seeps through there consciousness, their skins, and colours and flavours their world and their view of the world.

Such is the case for me. A round bottomed black iron pot that cooked many dishes the flavours for me are as sharp as the day they were first plated – pelau with pigeon peas, stewed chicken with a piece of pork for flavour, green fig and rice cookup. A porcelain cup with a hippopotamus on the front, a blue hippo that held my first easter egg – a Cadbury egg from my godmother. A small one-eyed teddy bear, a white bear with a green and white check body, both worse for wear, and only washed with love, soap never touching that, soap and blue that touched almost everything in a galvanise bucket next to the jooking board and the wash basin in the yard, next to the croton bushes that clothing took sun on – these call me from my childhood to find them and reclaim them from the recesses of time, to really see them and not just pass them by. It is as if they know that it is important to tell their story, to write it down, to paint them, because as the mind ages, it forgets; until waaaaay down the road, it remembers clearly distinctly sharply, for one minute all senses fire and the songs, the smells, the tastes, the feelings come back, and then they are gone, lost to time.

At home it is mango season. The rains and sun mix this year has created a bumper crop – but the trees around my house are peculiar – the mangoes ripen in green skins. The only sure way to know if the fruit or when it is ripe and ready for eating, is to check which ones the birds have already attacked. My grandmother used to select for me the ones the bird joked – her tree was a Julie, and the skins were a golden olive, perfumed that I will not forget – those were presented to me in a paper bag, with my name on it, apart from the perfect ovals in a washbasin for my siblings, and parents, and my cousins. Such was the measure of love that only the ripest, bird’s eye choice, was reserved for me.

My other scribbles as I fondly refer to them, post terror-of-conference, refer to among other things

chicken foot soup, and the first time I saw a chicken killed

a local gravedigger and a tale about some black plastic bags – the type you get everywhere here, when you go shopping, so no one can see what you have bought, so no one can mind your business – which took delivery of body parts it was his job to inter; at the end of which, damn the doctor, he needs a shot of rum

in days of drought, my kitchen looking like the long days and nights after that last hurricane, with every available container filled with water, covered and waiting, the water tasting as what it appears, brown with a whiff of bleach

the day the news came that my grandmother died, the smell of burnt sulphur from a match just struck, ignited in the mist of my tears, delightful images of childhood, love warmth and belonging.

|

| Me as the matchstick girl |

For this artist, a still life – fowl, shoes, flowers, fruit, fish – is a statement of a specific time, a scene where a person has just left to return momentarily, to answer the door, to greet a friend, to go lay down after a long day. The still life is the ultimate visualisation of everyday-ness. My work captures ‘still island life’ influenced by my current residence in Grenada influenced by my childhood home in neighbouring Trinidad. I ask what happens here?

The Thursday prior at the Saint Lucia High Commission in London, I attended the book launch of poet Kendel Hippolyte – his work is powerful stuff – we again met in Leeds. There I met our host Jeremy Poynting, founder of Peepal Tree Press, Grenadian author Jacob Ross of Pynter Bender fame, among many others, mostly new faces to me. On Day 2, I had the pleasure of lunching with both Jacob and Professor Kwame Dawes, whose key note lecture on ‘Redefining the Caribbean Literary Aesthetic for a New Century’, was entertaining, inspiring, and not at all as stuffy as the title sounds. They had both attended my panel on Day 1, and were kind with their comments on my presentation, Kwame paying a second close view of my lecture scribbles, and Jacob stating that I must now write every day, until this practice too, like my painting, becomes breathing.

|

| Me (still stunned) and Professor Dawes |

Liverpool: My visit to Liverpool was personal, but it was all about the art, architecture and history of the place. The Slave Museum was thrilling, and added much to my research of the history on Grenada…there are several mentions of Grenada there as part of the displays. More on that another time.