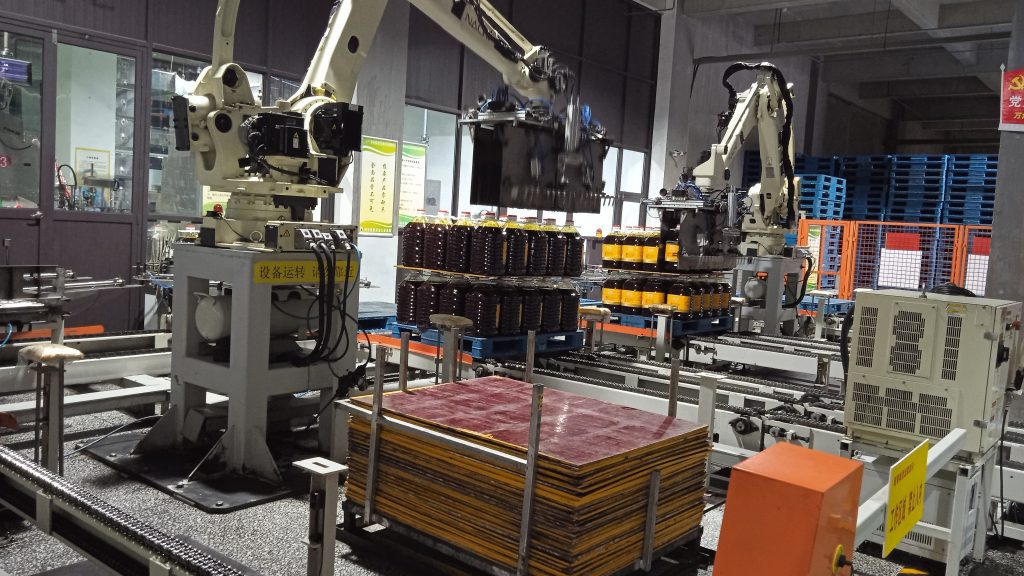

On Wednesday, 17 May, we visited the Xi’an Aiju Grain and Oil Industrial Group. Edible oils—rapeseed, soybean, sunflower, olive—flour and honey products from Kazakhstan were on display. The Group was founded in 1934 and also functions as a social and labour practice base for students.

China is accustomed to Central Asian products and the Group’s partnership with farmers in former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, projects inspired by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), support food security in Shaanxi province and economic security for the Central Asian farmers.

This week all eyes are on Xi’an and the China-Central Asia Summit underway on Thursday, 18 and Friday, 19. Xi’an is one of China’s 4 ancient capitals and was the historic starting point of the Silk Road, which allowed for movement of people, goods, and ideas between Europe and the Far East. In the year of the 10th anniversary of the BRI, this Summit is anticipated to deliver more tangible benefits to six nations’ peoples, with expanded cooperation in trade, agriculture and investment and reduced bureaucracy for trade facilitation. This is summed up in a headline on page 9 of the China Daily edition of Thursday, 18 May: Cooperation is an important part of neighbourhood diplomacy. I fully agree.

Walking through the Group’s warehouse and the adjacent retail outlet on site, I thought about a similar collaborative situation transplanted in the Caricom region. While I am happy for the Central Asian and Shaanxi peoples, writing from a small island Caribbean perspective, I am still concerned that we do not value similar neighbourhood diplomacy in trade, transport and reduced bureaucracy. Caricom is still unable to solve regional transport issues, and Trinidad’s honey issue, for example. Up to April 2023, the importation of honey into Trinidad and Tobago is still illegal, contrary to the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas. Grenada honey has been banned since the 1930s, and a shipment was destroyed in Trinidad in 2012.

Grenada’s Central Statistical Office states total imports in 2020 was EC$1,061 million. The World Bank lists Grenada’s exports (FOB) of US$25 million and imports (CIF) of US$395 million. The top 5 exported products and trade value were Mace (US$4,444.15 million); Wheat/meslin flour (US$3,489.36 million); Cocoa beans (US$1,890.05 million); preparations used in animal feed (US$1,624.44 million); Tuna (US$ 1,336.57 million). The top imported products and trade value were Petroleum, excluding crude (US$49,024.84 million); Digital auto data process machinery (US$8,703.81 million) and Chicken (US$8,453.51 million). Top export partners in 2020 were the United States, Trinidad and Tobago, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Antigua and Barbuda. Top import partners were the United States, Trinidad and Tobago, Cayman Islands, the United Kingdom and China.

In 2020, Grenada imported only US$ 15 million worth from China, with a partner share of 3.69%, compared to imports of US$ 154 million from the US, and a partner share of 38.94%. Is that due to transport distance or to lack of product awareness in China? After my visit to the Xi’an Aiju Grain and Oil Industrial Group, I am inspired to discover (i) if there is latitude for a collaborative approach of the nutmeg, cocoa and other associations in Grenada to offer a similar social and labour practice base for students, and (ii) what agriculture or fisheries products, or any other products for that matter, that Grenada can export to China’s domestic market. Who knows, through export to China, Grenada can indirectly export to Central Asia and elsewhere along the Silk Road routes.